For one of my first solar dyeing experiments, I used St Johns Wort, Hypericum, from the garden. My plant is one of the many varieties of Hypericum.

On 6 January I placed the buds, leaves and flowers separately in three glass jars, filled with tap water (Oxford bore) and placed a weight on the top to keep the unmordanted cotton cloths submerged.

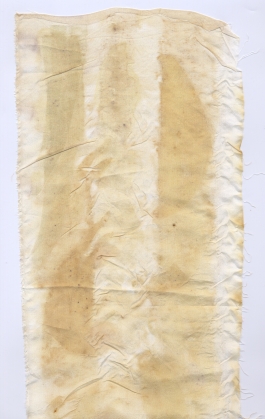

The following image is the dyed, scrunched up cotton from the jar that contained buds and two stones, one of which must have had a generous amount of iron in it as it introduced a black colour.

The resulting green, blue and black was very nice to see. The cotton from this and the next jar was removed on 17 January.

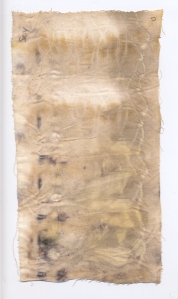

The jar with the chopped up hypericum leaves contained a Waimakariri river stone to weigh down the leaves and three folded and tied cotton bundles with different contents. In the photograph below, the top scrap of cotton was folded on its own. The lower scrap enclosed more hypericum leaves and some Acacia melanoxylon bark. The leaves in this bundle came through as a pale green-yellow, just visible in the image. The thin strip on the right is 300 gsm Fabriano paper, folded and placed in the jar with the bundles.

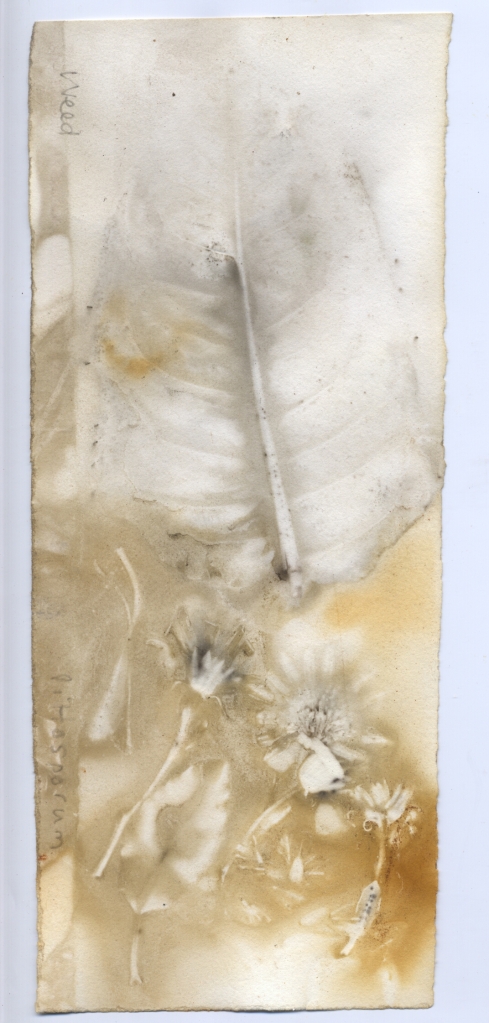

The third bundle containing flower buds is below. The yellow buds did not seem to change the colour; I do not know where the grey marks came from! Interesting that the iron caused such a different colour to appear in the first jar.

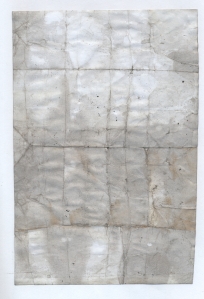

The third jar containing hypericum flowers and a piece of wire that I thought was copper was left until 28 January when I removed the cotton. Some brighter traces of yellow appear, perhaps through contact with the wire.

On 19 January I started to record my solar dyeing tests and to date I have 35 of them. No wonder I have not had a chance to sit down at the computer. The weather has been hot and mostly dry for about three weeks, even now at 5.51 pm it is 27 degrees C in the studio (built as a greenhouse). I recorded 47 degrees C one day on the shelf by the windows were I place my solar dye jars. The garden is full of flowers and I could certainly never need to go out further afield in search of material for dyeing. I hardly know where to start. I would prefer to concentrate on New Zealand native plants and have solar dyed with Harakeke the New Zealand flax plant – Phormium cookianum; Griselinea littorals; Hebe; and Wineberry – Aristotelia serrata.

I have been reading Richard Mabey’s book Weeds; How Vagabond Plants Gatecrashed Civilisation and Changed the Way We Think About Nature, published in 2010. Chance and serendipity are rife here at the moment – I found this book in the library by chance – and I was also concurrently very curious about a weed that was new to me. I eventually found this plant on the internet by using the search terms ‘tiny white flower weed’. The plant is called Galinsoga parviflora and has the common names of Gallant Soldier or Potato Weed. Well, it is growing in the vegie patch and appeared last season – near the potatoes. Then I discover from the Contents that Mabey’s book has a chapter entitled Gallant-soldier! It so happens that this plant, a member of the daisy family, arrived at Kew Gardens in 1793 from Peru and was named after the ‘splendidly ennobled’ Spanish botanist Don Mariano Martinez de Galinsoga. This plant has the tiny-est flower I have ever seen. It escaped Kew Gardens in the 1860s and eventually found its way to my garden.

Another serendipitous moment arrived when I read in this book that in 1748 ‘a celebrated [British agricultural] improver, William Ellis, who farmed at Little Gaddesden in the Chilterns […] was experimenting with different methods of weed control and pasture management’. Ellis used clover as an effective way of controlling weeds. This nitrogenous crop could be ploughed in so was also a great cost saver as hand weeding would not be required. I expect my ancestors from Little Gaddesden took to straw-plaiting to supplement their incomes, no longer being required to weed the Corn (wheat) fields. Actually, we have also used clover as a weed suppressant – we have a bricked area that we despaired of – after two years hand weeding between the bricks we once tried the chemical way but not really wanting to do this gave that idea up pretty fast (and it didn’t work really for the weeds came back quickly). We finally decided to just mow it! It works wonderfully, and is a haven for the bees as the clover is taking over.

Much to my comfort, Mabey also talks about Hypericum perforatum. “Each leaf is covered in tiny transparent dots (the perforations of the Latin name…) and held up against the sky the sun’s rays prick through, like dapple in a springtime wood.” A good connection with embroidery there…

This is miles away from eco-print and solar dyeing… and the dye from Galinsoga is a pale straw colour.